Description

Dan Casey saw the bird first, shimmering against the distant horizon like a desert mirage. From his perch, about two miles away, it was little more than a flicker of motion sketched across a cerulean sky. That was all he needed.

“It’s a sharp-shinned hawk,” he barked after a perfunctory glance through his binoculars.

Gathered behind Casey, a handful of birders squinted into their own specs.

“It’s just a speck,” huffed one. “How can you tell?”

“The way it flaps,” deadpanned Casey. “The fact that I’ve probably seen 10,000 of them from this spot.”

That may not be an exaggeration. For the past 18 autumns, the 70-year-old retired ornithologist has made weekly pilgrimages to the same spot on a ridgeline high above the Jewel Basin. On an average visit, he might spend upwards of six hours nestled in the krummholz and bear grass, recording the age and species of each raptor that flies by, bound for warmer overwintering grounds in the southern United States or Central America.

It’s a tedious job, but invaluable in researchers’ attempts to better understand how native populations of eagles, hawks, falcons, kestrels and harriers are faring.

As a child, he recalled visiting hawk watch sites along the East Coast. Perched on mountaintops in key migratory corridors, biologists and citizen scientists would spend the fall recording daily counts of more than a dozen species of hawks, eagles, falcons and other raptors.

Decades later, Casey hatched the idea for a similar site after spotting a few raptors on a hike in the Jewel Basin. On reflection, Casey realized that he and his wife nearly always encountered some sort of hawk, eagle or falcon on their autumn hiking excursions.

He hypothesized the peaks in the Swan Range formed a sort of atmospheric freeway for raptors migrating south for the winter from Canada and Alaska. The steep slopes and deep valleys sculpt air currents into a series of updrafts and thermals that large birds can easily soar on — minimal flapping required. The birds likely also use the ridgeline as a navigational tool to help keep them on their migratory path south.

In 2007, Casey started experimenting with different ridgelines around the Jewel Basin, searching for the perfect location to stage the hawk watch. On his first visit to the chosen site, about a half mile north on the ridgeline from Mount Aneas, Casey counted 160 raptors in the span of four hours. He recalled turning to his wife, who had accompanied him on the trip, and exclaiming, “Oh, this is probably going to work!”

Flathead Audubon started conducting regular migration surveys in the Jewel Basin the next year. Beginning in late August, at least one volunteer ascends the mountain each day to count migrating raptors. The tallies are automatically uploaded to an online database called HawkCount, which houses data from more than 300 hawk watches across North America.

“Data from one site is not that meaningful,” explained Casey.

Inclement weather or poor visibility can easily skew a daily count, making day-to-day trends difficult to discern. Combining data from multiple sites and years mitigates those factors and helps bring long-term patterns into focus. The more data that is gathered, the better chance scientists have of seeing issues as they arise.

“Sometimes, you don’t even know the questions you need to answer,” said Casey.

He pointed to golden eagles as one example. Data collected from hawk watches across the western United States points to widespread population declines, possibly as a result of habitat loss and conflict with humans. In the mid-1990s, biologists recorded about 2,000 golden eagles on fall migrations past Mount Brown in Glacier National Park. Counts from the past four years have averaged about 1,500 golden eagles.

Casey has spotted his fair share of eagles in the Jewel Basin, but he said the most frequent flyers are sharp-shinned hawks. When migration peaks in late September, more than 100 "sharpies” might whiz by the ridgeline in a single day.

Though slight in stature, sharp-shinned hawks, like many raptors, are notoriously territorial. Casey uses a decoy great-horned owl to lure passing birds closer to the ridgeline, where he can get a better look at their markings and size.

Over the course of 18 years, Casey and the other volunteers at the Jewel Basin Hawk Watch have counted and identified more than 50,000 individual raptors. The current record for a daily count, set on Sept. 21, 2020, included 595 birds from 12 different species, including sharp-shinned hawks, Cooper’s hawks, red-tailed hawks, peregrine falcons, bald eagles, golden eagles, northern harriers and American kestrels.

In the future, Casey said he would like to expand the efforts in the Jewel Basin to include banding for some key species. Researchers can use the numbered bands, which are attached to a bird’s leg, to track the movement, reproductive success and survival rate of individual birds.

This year, though, Casey let the birds come to him.

Reclined in his camp chair on a sunlit section of the ridgeline, he watched the steady approach of the sharp-shinned hawk. From a bare pencil-line sketch, the bird grew a head and wings and then feathers. Then, for seemingly no reason, the hawk dipped to the left. It careened into the neighboring valley, out of sight.

“Oh, come one and quit farting around so I can count you already,” Casey mumbled, binoculars still pressed firmly into his eye sockets.

He lowered them just in time to see the hawk pop over the ridgeline, a few feet away. Rocketing up from the valley, speckled belly on full display, the bird angled itself toward the plastic owl decoy. A crash seemed inevitable, but, at the last moment, the hawk tipped its wings and juked upwards.

Another recalibration set the raptor back on course, toward the southern horizon. It disappeared the same way it emerged, a flash of auburn melting into distant blues.

Reporter Hailey Smalley can be reached at 758-4433 or [email protected].

A sharp-shinned hawk flies high above the Jewel Basin Hawk Watch on Tuesday, Sept. 16. (Casey Kreider/Daily Inter Lake)

A sharp-shinned hawk flies high above the Jewel Basin Hawk Watch on Tuesday, Sept. 16. (Casey Kreider/Daily Inter Lake)

Casey Kreider

Dan Casey, with the Flathead Audubon Society, scans the skies and ridgetops around the Picnic Lakes monitoring raptor migration at the Jewel Basin Hawk Watch on Tuesday, Sept. 16. (Casey Kreider/Daily Inter Lake)

Dan Casey, with the Flathead Audubon Society, scans the skies and ridgetops around the Picnic Lakes monitoring raptor migration at the Jewel Basin Hawk Watch on Tuesday, Sept. 16. (Casey Kreider/Daily Inter Lake)

Casey Kreider

A mountain goat explores around the Jewel Basin Hawk Watch site on Tuesday, Sept. 16. (Casey Kreider/Daily Inter Lake)

A mountain goat explores around the Jewel Basin Hawk Watch site on Tuesday, Sept. 16. (Casey Kreider/Daily Inter Lake)

Casey Kreider

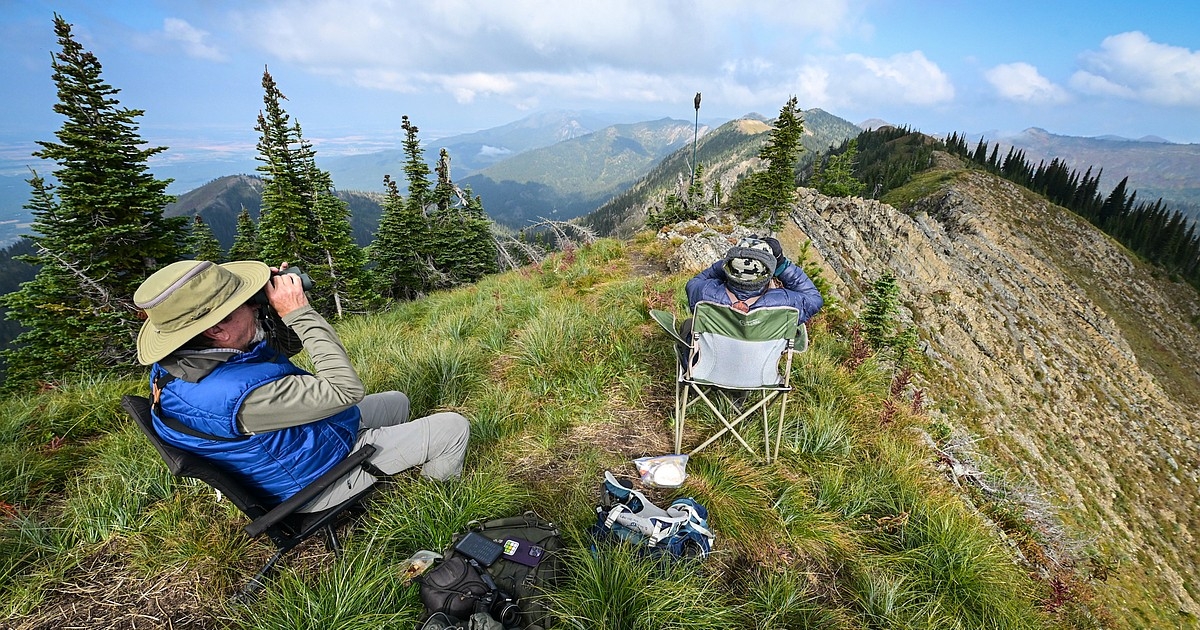

Dan Casey, right, and Denny Olson, with the Flathead Audubon Society, scan the skies and ridgetops monitoring raptor migration at the Jewel Basin Hawk Watch on Tuesday, Sept. 16. (Casey Kreider/Daily Inter Lake)

Dan Casey, right, and Denny Olson, with the Flathead Audubon Society, scan the skies and ridgetops monitoring raptor migration at the Jewel Basin Hawk Watch on Tuesday, Sept. 16. (Casey Kreider/Daily Inter Lake)

Casey Kreider

A hawk perches on a distant tree as members of the Flathead Audubon Society monitor raptor migration at the Jewel Basin Hawk Watch on Tuesday, Sept. 16. (Casey Kreider/Daily Inter Lake)

A hawk perches on a distant tree as members of the Flathead Audubon Society monitor raptor migration at the Jewel Basin Hawk Watch on Tuesday, Sept. 16. (Casey Kreider/Daily Inter Lake)

Casey Kreider

A sharp-shinned hawk flies high above the Jewel Basin Hawk Watch on Tuesday, Sept. 16. (Casey Kreider/Daily Inter Lake)

A sharp-shinned hawk flies high above the Jewel Basin Hawk Watch on Tuesday, Sept. 16. (Casey Kreider/Daily Inter Lake)

Casey Kreider

News Source : https://dailyinterlake.com/news/2025/oct/19/eagle-eyed-volunteers-track-migratory-raptors-in-Jewel-Basin/

Other Related News

10/19/2025

When Carolyn Rutherford began teaching in 1996 she wanted to help people live better live...

10/19/2025

Filming has taken place in Western Montana for a new short film backed by the Montana Big...

10/19/2025

In the dark of night a kayak glides along the shoreline Headlamps cut through the darknes...

10/19/2025

Detention officers stood alert next to an open cell in the jails medical wing Tasers read...

10/19/2025